Het arrangement Alarming Behaviour is gemaakt met Wikiwijs van Kennisnet. Wikiwijs is hét onderwijsplatform waar je leermiddelen zoekt, maakt en deelt.

- Auteur

- Laatst gewijzigd

- 05-11-2019 21:15:03

- Licentie

-

Dit lesmateriaal is gepubliceerd onder de Creative Commons Naamsvermelding-GelijkDelen 3.0 Nederland licentie. Dit houdt in dat je onder de voorwaarde van naamsvermelding en publicatie onder dezelfde licentie vrij bent om:

- het werk te delen - te kopiëren, te verspreiden en door te geven via elk medium of bestandsformaat

- het werk te bewerken - te remixen, te veranderen en afgeleide werken te maken

- voor alle doeleinden, inclusief commerciële doeleinden.

Meer informatie over de CC Naamsvermelding-GelijkDelen 3.0 Nederland licentie.

This course is a production of the Integral Safe Higher Education program, with the cooperation of the National Training Institute combating radicalization, Flooow (e-learning production) and Zelfspot (audiovisual productions). For the compilation of this course, use was made of train-the-trainer material from NCTV and ISDEP (Improving Security Through Democratic Participation), adjustments aimed at higher education and proprietary material.

All information about existing persons is based on public sources.

Credit icons under GPL-license:

Nick Roach, http://www.elegantthemes.com/

Aanvullende informatie over dit lesmateriaal

Van dit lesmateriaal is de volgende aanvullende informatie beschikbaar:

- Toelichting

- Deze cursus is een productie van het programma Integraal Veilig Hoger Onderwijs (opdrachtgever), met medewerking van het Rijksopleidingsinstituut tegengaan radicalisering, Flooow (e-learning productie) en Zelf-spot (audiovisuele producties). Voor vragen over deze e-learning kun je contact opnemen met het programma Integraal Veilig Hoger Onderwijs via info@integraalveilig-ho.nl. Alle informatie over bestaande personen is gebaseerd op openbare bronnen.

- Leerniveau

- WO - Bachelor; WO - Master; HBO - Master; HBO - Bachelor;

- Eindgebruiker

- leraar

- Moeilijkheidsgraad

- makkelijk

- Studiebelasting

- 2 uur 30 minuten

- Trefwoorden

- aggressie, extremisme, gedrag, hoger, onderwijs, radicalisering, studenten, suicide, zelfmoord, zorgwekkend

Changes in a student’s behaviour will also be visible at school. We call these changes ‘indicators’. The first indicator is an obvious one: is the student falling behind? An unusual deviation from the norm could be an indicator. In 99.9% of cases there will be no cause for concern, but it is a good idea to talk to the student.

Changes in a student’s behaviour will also be visible at school. We call these changes ‘indicators’. The first indicator is an obvious one: is the student falling behind? An unusual deviation from the norm could be an indicator. In 99.9% of cases there will be no cause for concern, but it is a good idea to talk to the student.

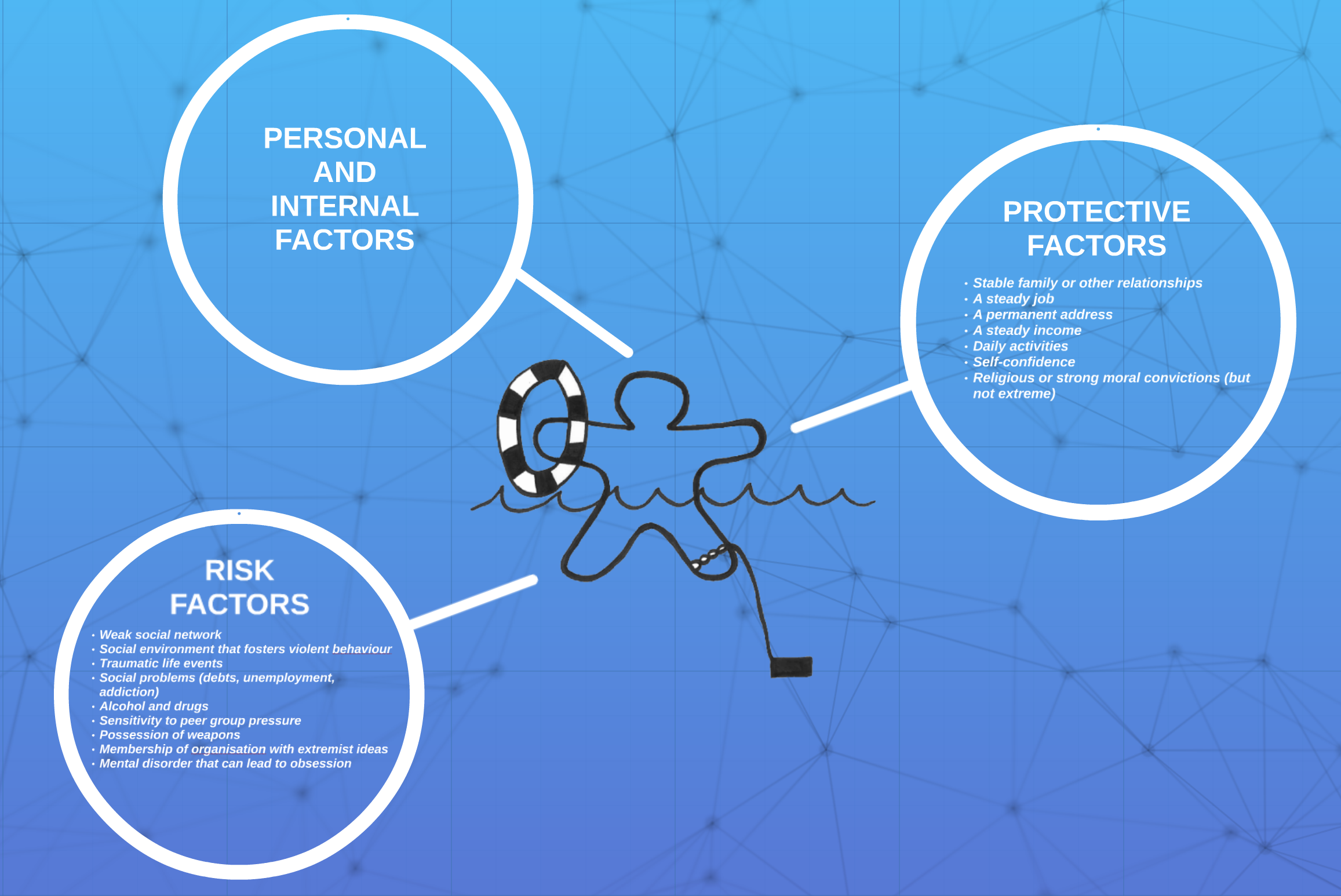

Imagine the following scenario. You have strong opinions about international conflicts and follow the news every day. Then one day a close relative dies suddenly and you lose your job around the same time. Are these experiences likely to lead to alarming behaviour? Probably not. But in combination with other factors, difficult experiences like these could trigger high-risk ideas or even actions.

Imagine the following scenario. You have strong opinions about international conflicts and follow the news every day. Then one day a close relative dies suddenly and you lose your job around the same time. Are these experiences likely to lead to alarming behaviour? Probably not. But in combination with other factors, difficult experiences like these could trigger high-risk ideas or even actions.

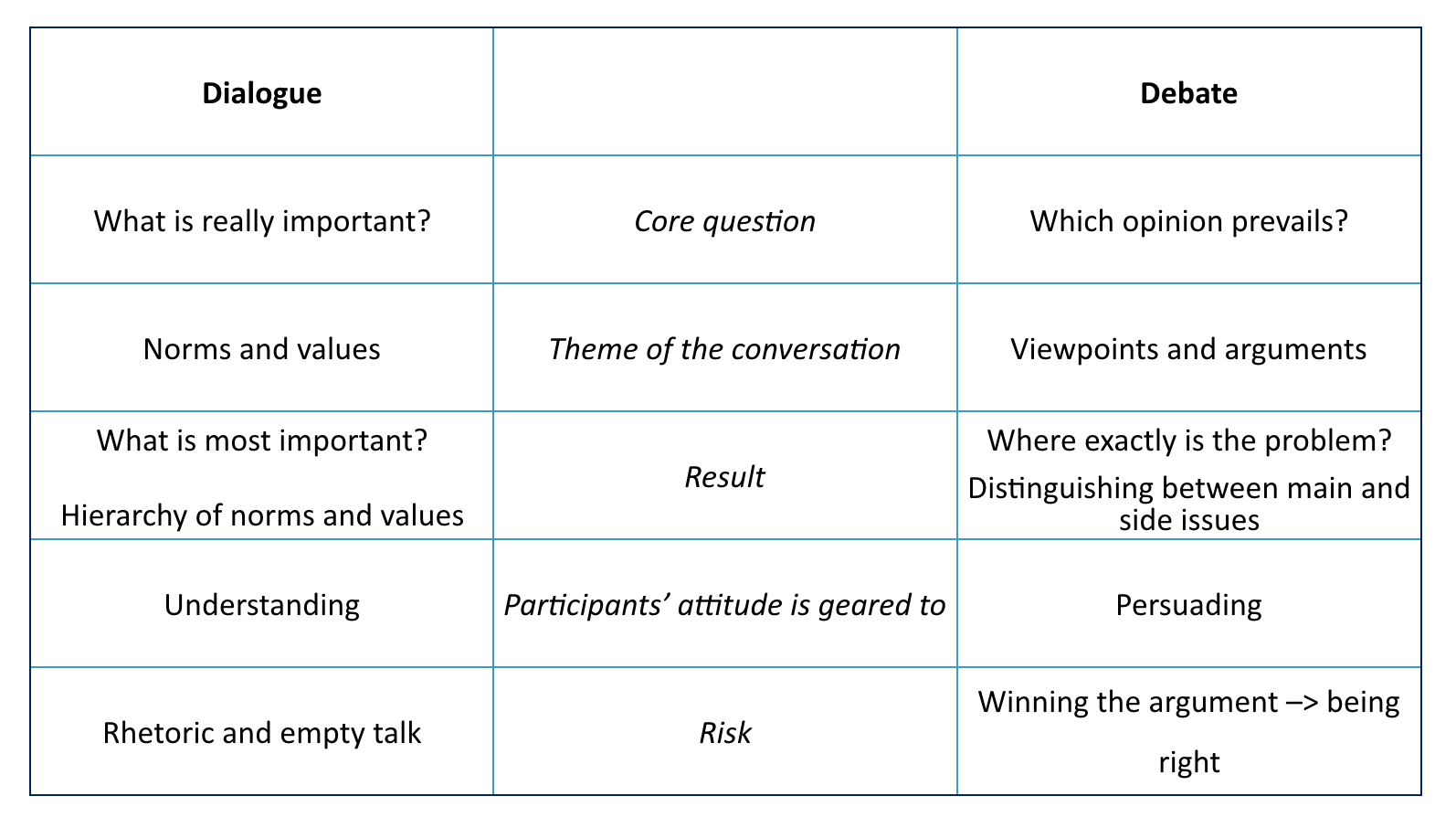

Some might say that the truth is the truth and students have the right to believe in conspiracy theories. But in these cases you really need to know what you’re doing, because it’s the thin edge of the wedge if all truth is relative. In practice, this is generally not the best way to gain your students’ trust, while gaining their trust is essential. How do you do that?

Some might say that the truth is the truth and students have the right to believe in conspiracy theories. But in these cases you really need to know what you’re doing, because it’s the thin edge of the wedge if all truth is relative. In practice, this is generally not the best way to gain your students’ trust, while gaining their trust is essential. How do you do that?

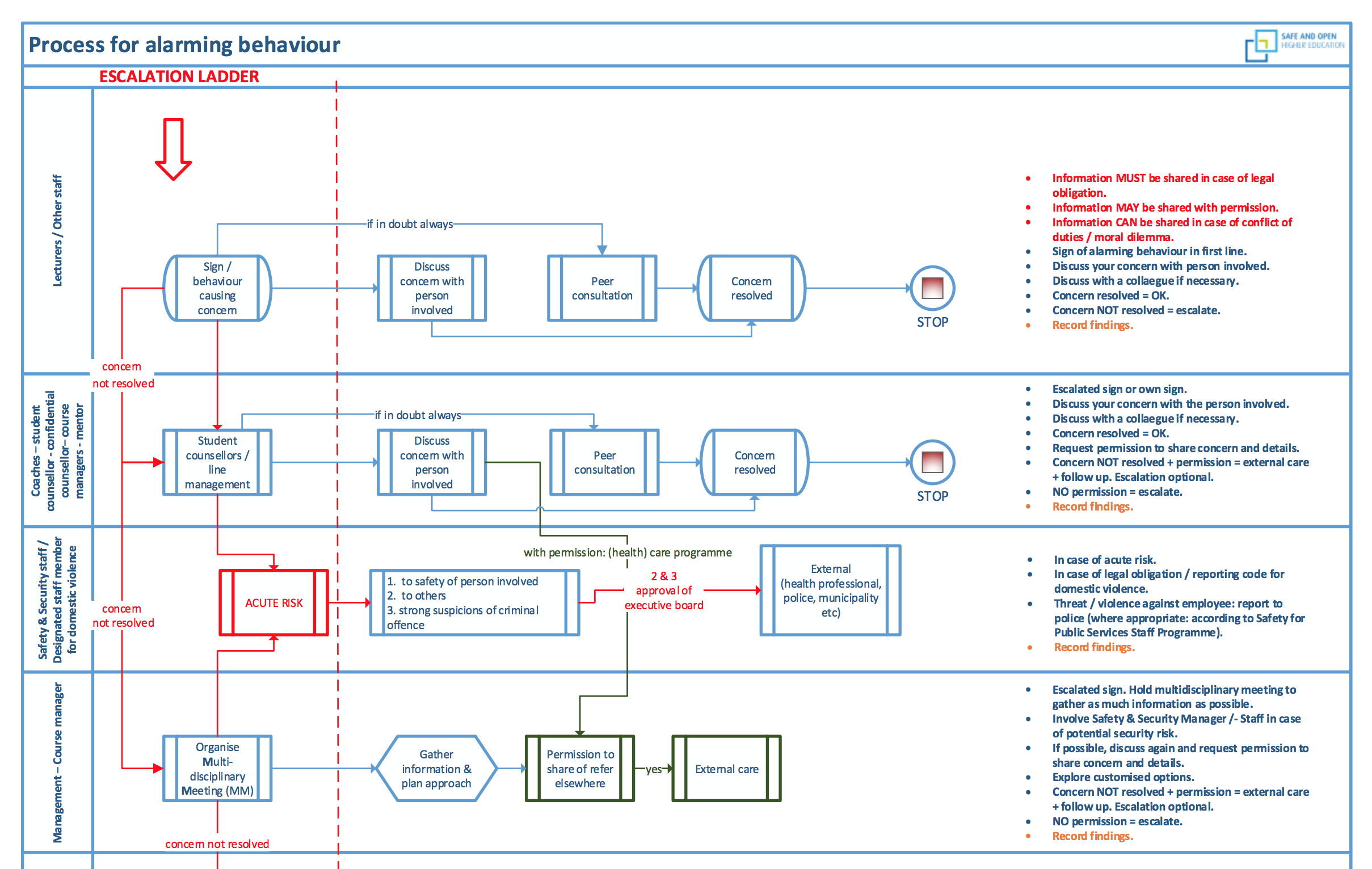

What should you do if your first talk with the student doesn’t lead to a solution? Or if there is an imminent threat calling for immediate action? Then it is important to know what steps have been agreed in your organisation, and which escalation process should be followed. The steps to be taken and your role in the process are set out in what we call a ‘ladder of escalation’.

What should you do if your first talk with the student doesn’t lead to a solution? Or if there is an imminent threat calling for immediate action? Then it is important to know what steps have been agreed in your organisation, and which escalation process should be followed. The steps to be taken and your role in the process are set out in what we call a ‘ladder of escalation’.

On 29 January 2015, a young man with a gun in his hand walked into the building of Dutch public broadcaster NOS in the Media Park in Hilversum. He handed a letter to the doorman in which he demanded air time so that he could warn the nation of a dangerous conspiracy. Five minutes later, the young man, whose name was Tarik Zahzah, was overpowered and arrested by the police.

On 29 January 2015, a young man with a gun in his hand walked into the building of Dutch public broadcaster NOS in the Media Park in Hilversum. He handed a letter to the doorman in which he demanded air time so that he could warn the nation of a dangerous conspiracy. Five minutes later, the young man, whose name was Tarik Zahzah, was overpowered and arrested by the police.

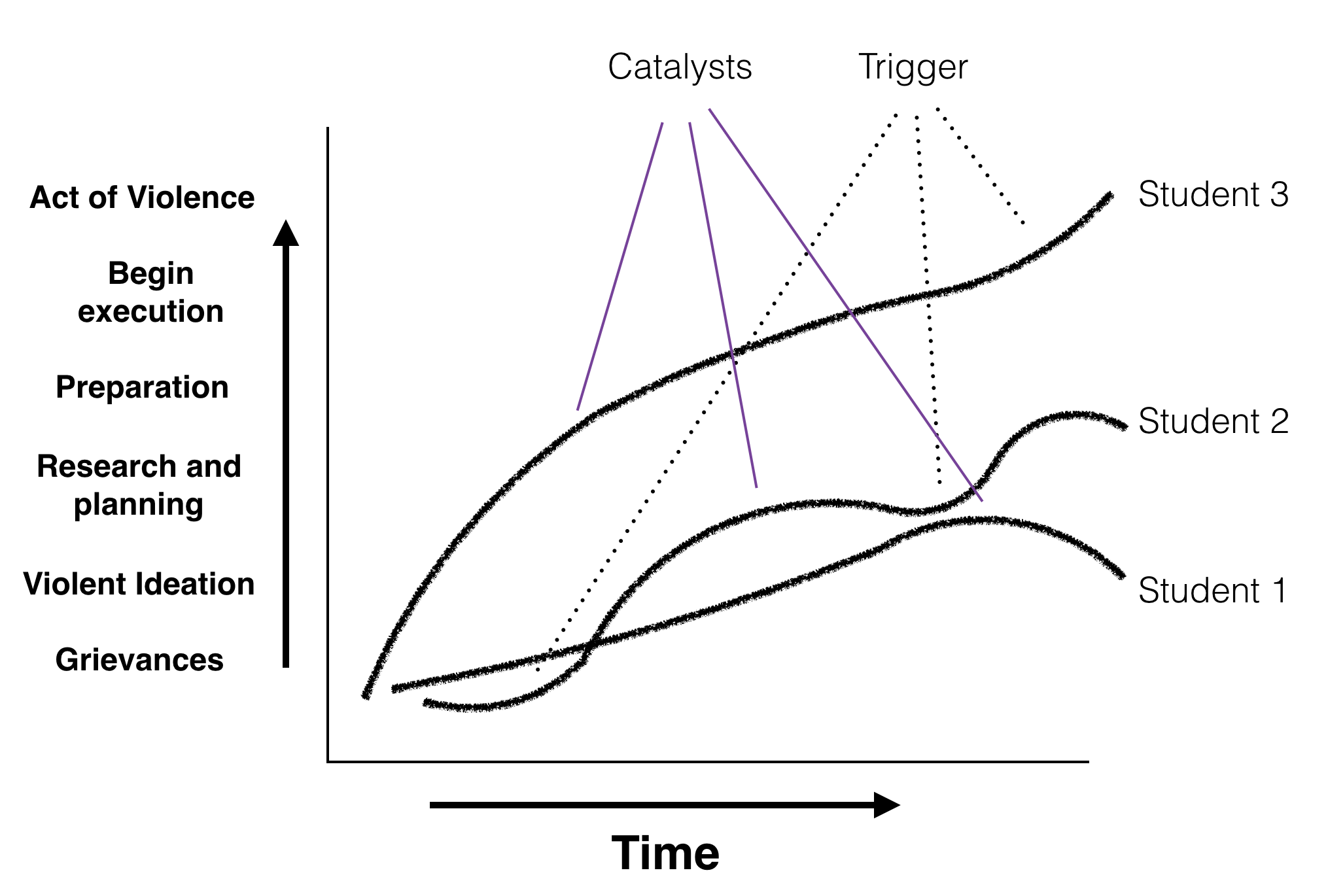

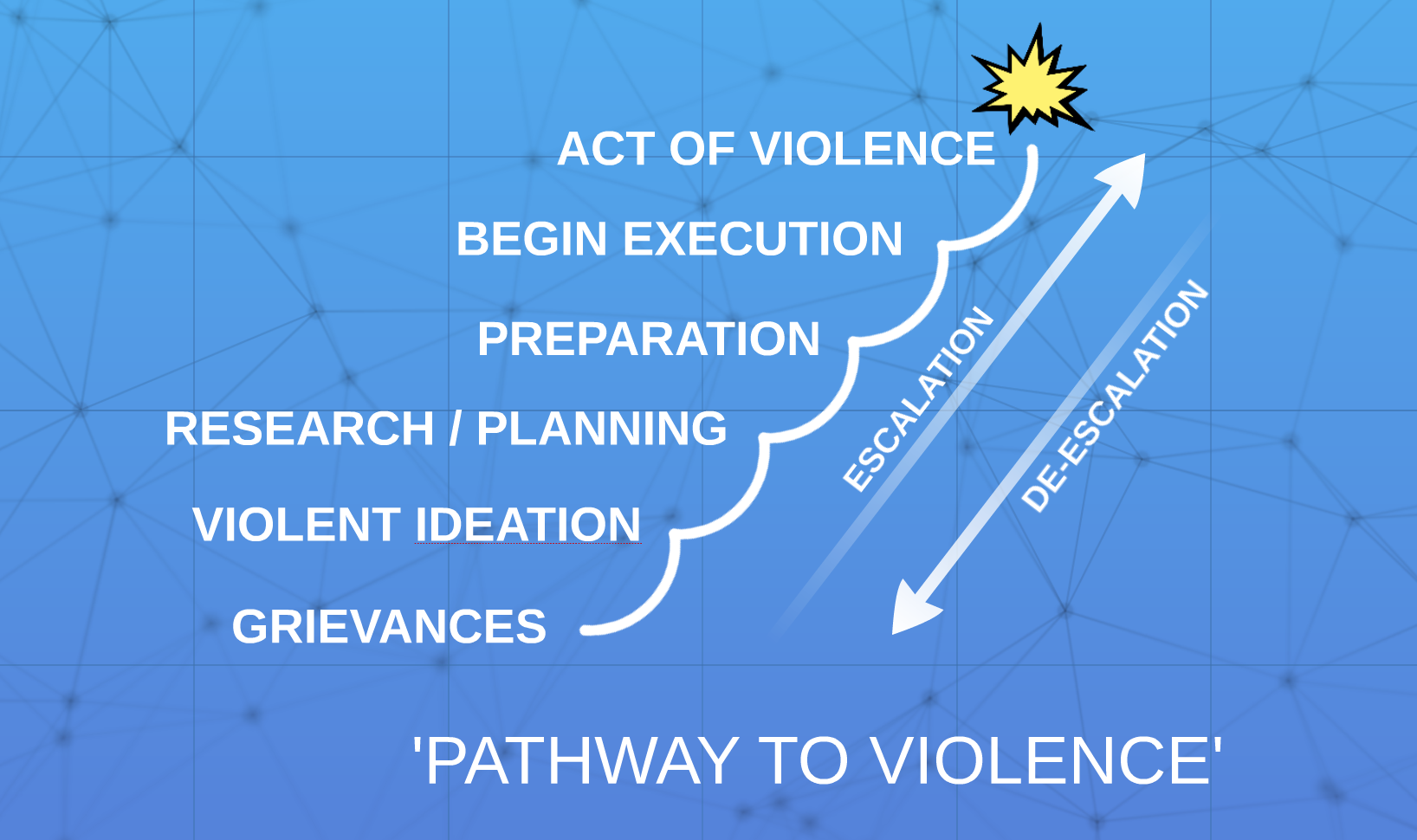

"I have to do something!" This appears to be the feeling that generally leads to the next step on the pathway to violence, ideation. While most people are able to shake off their grievances or frustrations fairly easily, a few individuals are unable to do so. An idea takes hold in their mind, and they find it increasingly difficult to let it go.

"I have to do something!" This appears to be the feeling that generally leads to the next step on the pathway to violence, ideation. While most people are able to shake off their grievances or frustrations fairly easily, a few individuals are unable to do so. An idea takes hold in their mind, and they find it increasingly difficult to let it go. The next stage on the pathway to violence is planning and preparing the eventual action. At this point, alarming behaviour begins to evolve into high-risk behaviour, which becomes increasingly difficult to stop from this stage. The ideas crystallise: the individual investigates how others carried out similar plans, and sets out a timetable.

The next stage on the pathway to violence is planning and preparing the eventual action. At this point, alarming behaviour begins to evolve into high-risk behaviour, which becomes increasingly difficult to stop from this stage. The ideas crystallise: the individual investigates how others carried out similar plans, and sets out a timetable.

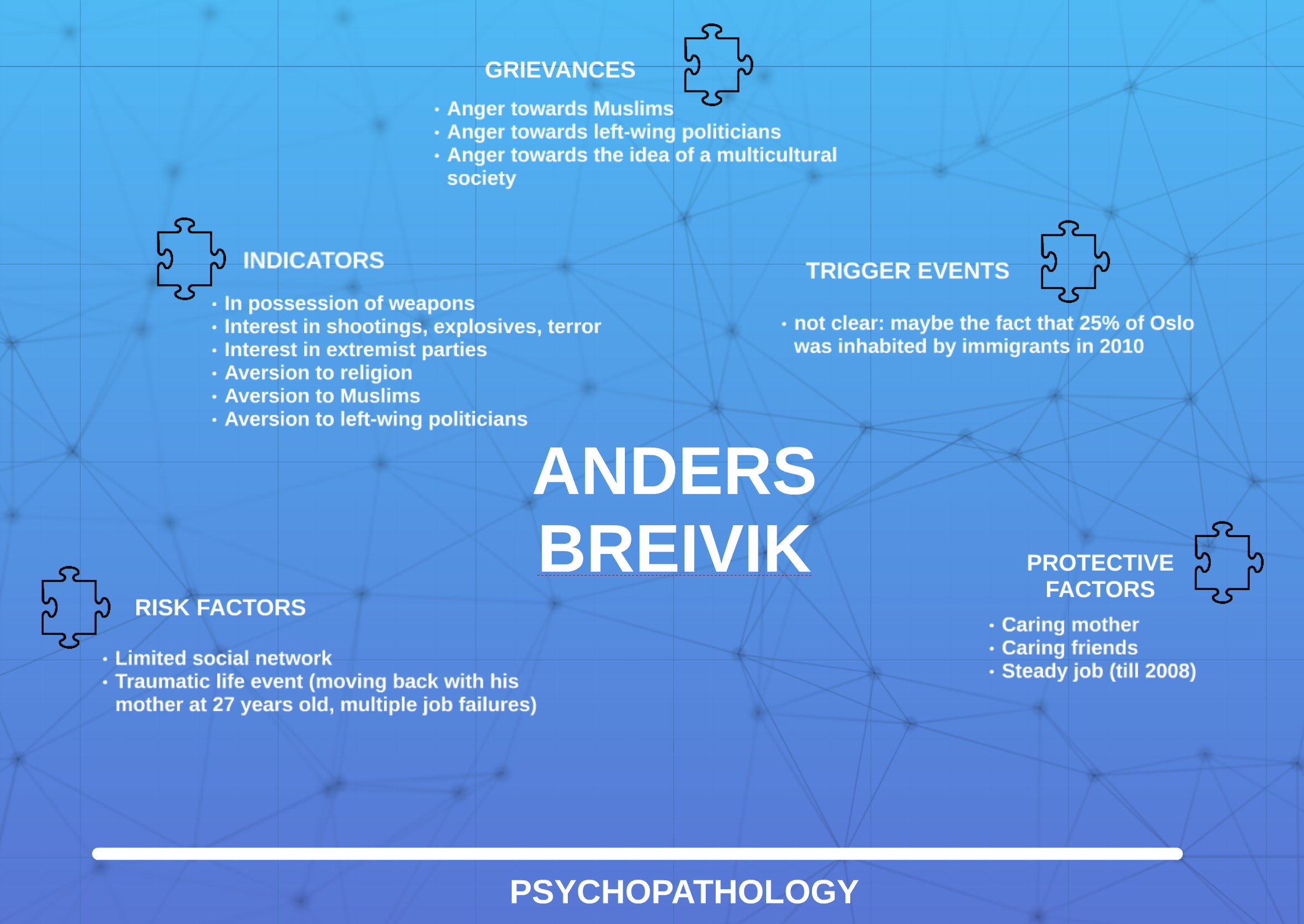

In this module you have experienced how alarming behaviour by two individuals from two very different backgrounds can escalate and culminate in an attack or membership of a violent group or network. These are just two examples. In the three practice-oriented modules we dealt with cases of students displaying alarming behaviour in the form of politically-motivated violence, a suicide threat and aggression caused by a psychological disorder.

In this module you have experienced how alarming behaviour by two individuals from two very different backgrounds can escalate and culminate in an attack or membership of a violent group or network. These are just two examples. In the three practice-oriented modules we dealt with cases of students displaying alarming behaviour in the form of politically-motivated violence, a suicide threat and aggression caused by a psychological disorder.