Het arrangement Digital eyes on citizens h45 is gemaakt met Wikiwijs van Kennisnet. Wikiwijs is hét onderwijsplatform waar je leermiddelen zoekt, maakt en deelt.

- Auteur

- Laatst gewijzigd

- 21-07-2025 09:25:48

- Licentie

-

Dit lesmateriaal is gepubliceerd onder de Creative Commons Naamsvermelding-GelijkDelen 4.0 Internationale licentie. Dit houdt in dat je onder de voorwaarde van naamsvermelding en publicatie onder dezelfde licentie vrij bent om:

- het werk te delen - te kopiëren, te verspreiden en door te geven via elk medium of bestandsformaat

- het werk te bewerken - te remixen, te veranderen en afgeleide werken te maken

- voor alle doeleinden, inclusief commerciële doeleinden.

Meer informatie over de CC Naamsvermelding-GelijkDelen 4.0 Internationale licentie.

Aanvullende informatie over dit lesmateriaal

Van dit lesmateriaal is de volgende aanvullende informatie beschikbaar:

- Toelichting

- Deze les valt onder de arrangeerbare leerlijn van de Stercollectie voor Engels voor havo, leerjaar 4 en 5. Dit is thema 'Societies'. Het onderwerp van deze les is: Digital eyes on citizens. In deze les gaat het over de overheid dat (via digitale wegen) zicht houdt op de burgers en hierbij informatie verzameld. Hier wordt China als voorbeeld gegeven.

- Leerniveau

- HAVO 4; HAVO 5;

- Leerinhoud en doelen

- Engels;

- Eindgebruiker

- leerling/student

- Moeilijkheidsgraad

- gemiddeld

- Studiebelasting

- 4 uur 0 minuten

- Trefwoorden

- arrangeerbaar, china, digital eyes on citizens, engels, h45, informatie verzamelen, overheid, stercollectie

In this next lesson is Digital eyes on citizens.

In this next lesson is Digital eyes on citizens.

Ask and answer these questions with your partner.

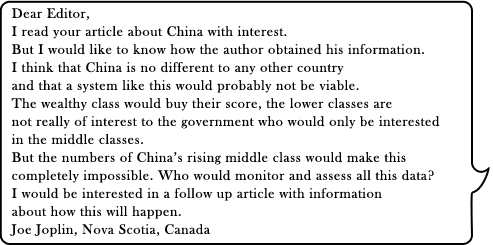

Ask and answer these questions with your partner. Proposed system of personal data will record ‘trustworthiness’ rating

Proposed system of personal data will record ‘trustworthiness’ rating

Writing Task

Writing Task