The arrangement Rotterdam UAS Literature Research Training is made with Wikiwijs of Kennisnet. Wikiwijs is an educational platform where you can find, create and share learning materials.

- Author

- Last modified

- 02-12-2025 14:23:23

- License

-

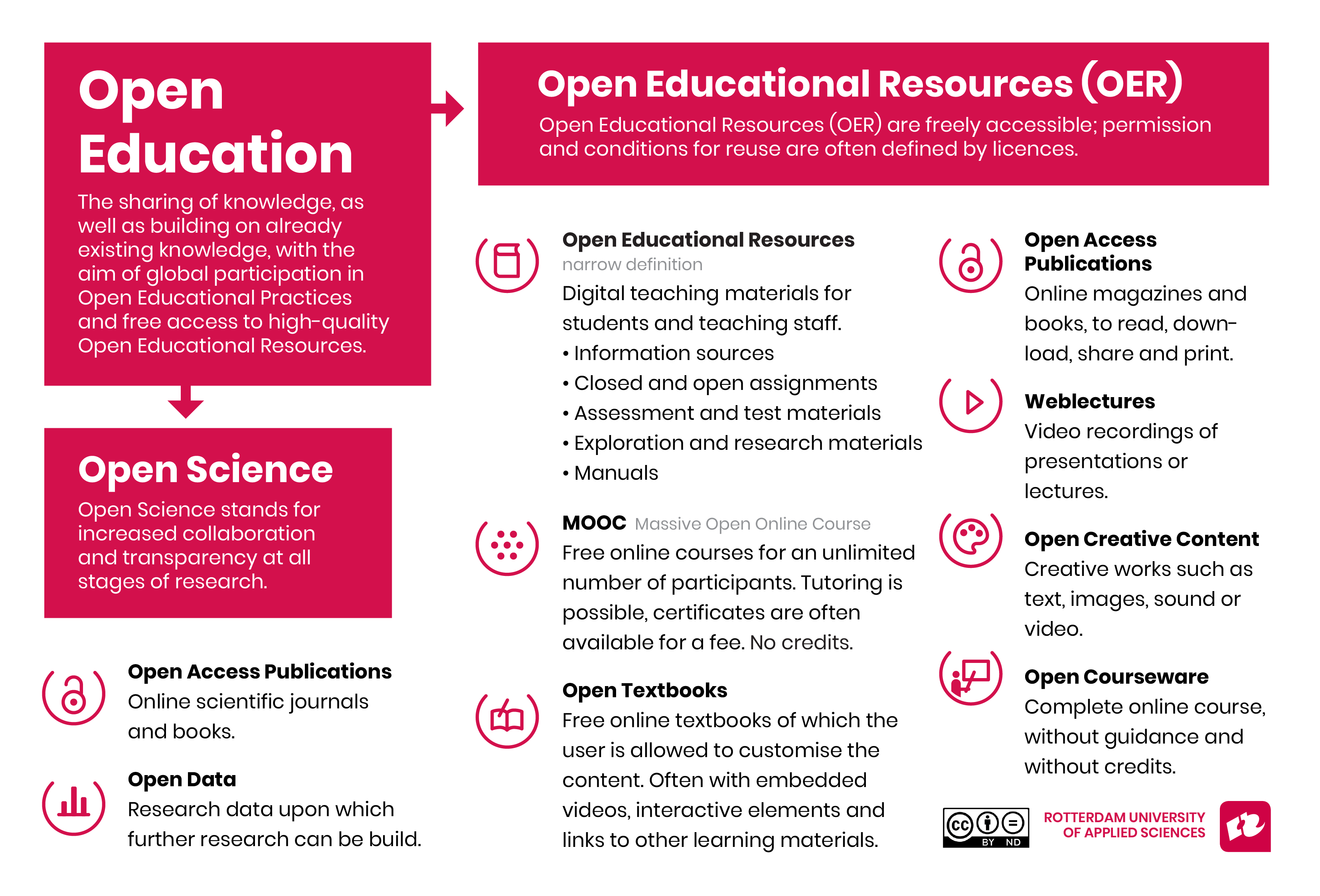

This learning material is published under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license. This means that, as long as you give attribution, you are free to:

- Share - copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format

- Adapt - remix, transform, and build upon the material

- for any purpose, including commercial purposes.

More information about the CC Naamsvermelding 4.0 Internationale licentie.

Bronnen:

Libguides RUG: https://libguides.rug.nl/c.php?g=531668&p=3637442

Stappenplan Zoekstrategie, Mediatheek Hogeschool Rotterdam: Zoekstrategie

Wikiwijsarrangement InHolland: https://maken.wikiwijs.nl/69846/Informatievaardigheid__een_mooie_start

Zoeklicht HvA: Zoeklicht - Hogeschool van Amsterdam

Zoekplan, NHL Stenden Hogeschool: http://informatievaardigheden.nhlstenden.com

Additional information about this learning material

The following additional information is available about this learning material:

- Description

- There are more than a billion websites and more than 800,000 books are published each year. But where exactly can you find the information you need? In this training you will learn how to find reliable information relevant to your studies in a smart and fast way.

- Education level

- HBO - Master; HBO - Bachelor;

- End user

- leerling/student

- Difficulty

- gemiddeld

- Keywords

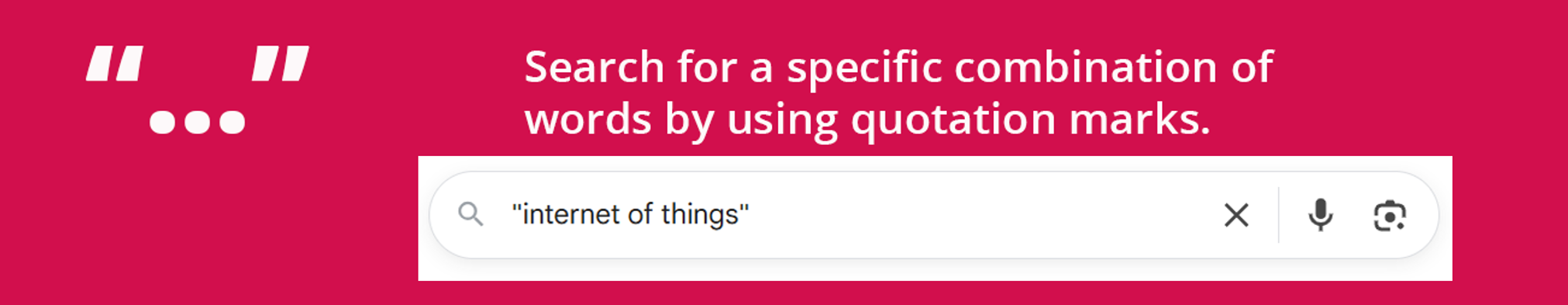

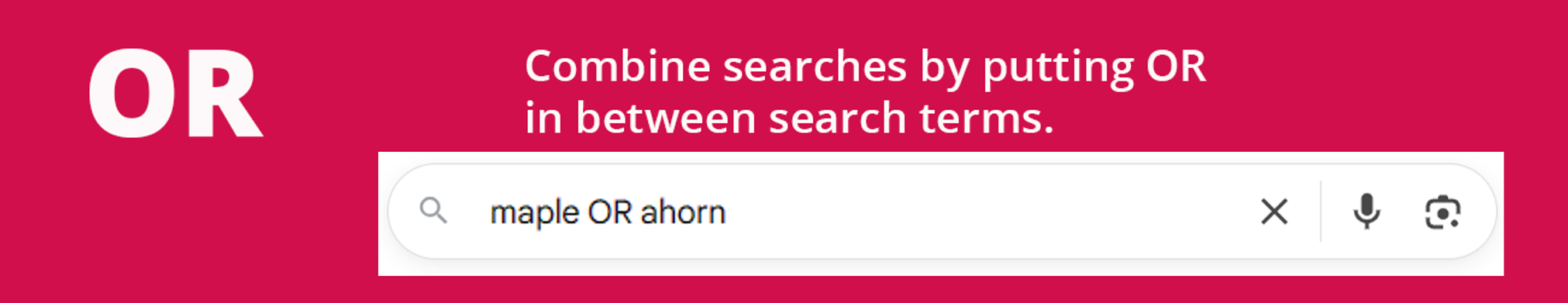

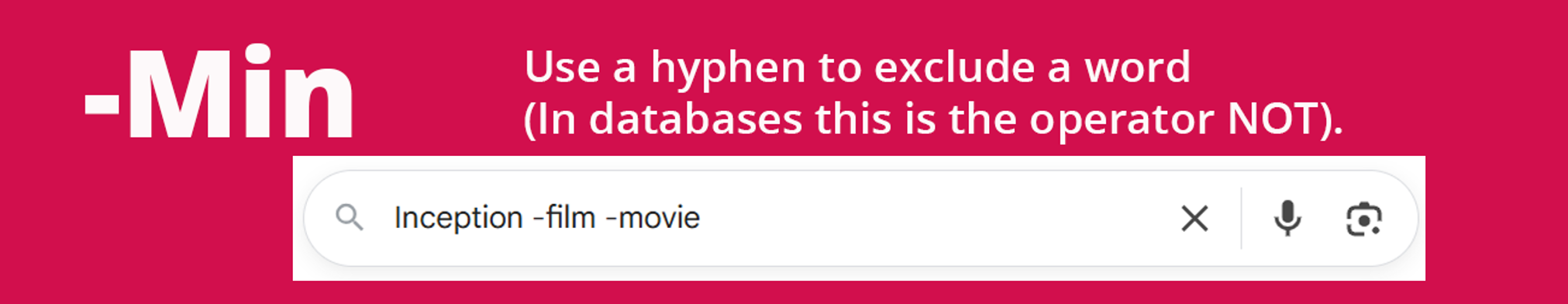

- information literacy, orientate, quotation of sources, search methods, search techniques

Used Wikiwijs arrangements

Team Informatievaardigheid Hogeschool Rotterdam. (2022).

Training literatuuronderzoek Hogeschool Rotterdam

https://maken.wikiwijs.nl/164140/Training_literatuuronderzoek_Hogeschool_Rotterdam

That is why you formulate a number of sub-questions based on your main research question. Sub-questions allow you to divide your complex main research question into smaller subjects. Each sub-question contributes to answering your main research question. Once you have answered all the sub-questions, it should be possible to answer your main research question as well.

That is why you formulate a number of sub-questions based on your main research question. Sub-questions allow you to divide your complex main research question into smaller subjects. Each sub-question contributes to answering your main research question. Once you have answered all the sub-questions, it should be possible to answer your main research question as well.

.

.

A referencing style is a set of rules for how to cite a source reference. There are many different referencing styles, but at Rotterdam University of Applied Sciences, APA is the most commonly used . Other referencing styles are: IEEE, MLA, Harvard and Leidraad voor juridische auteurs (Guidelines for Legal Authors). Whichever referencing style you use, be consistent and stick to one style.

A referencing style is a set of rules for how to cite a source reference. There are many different referencing styles, but at Rotterdam University of Applied Sciences, APA is the most commonly used . Other referencing styles are: IEEE, MLA, Harvard and Leidraad voor juridische auteurs (Guidelines for Legal Authors). Whichever referencing style you use, be consistent and stick to one style.