The arrangement Finding Scientific Literature Step by Step (FSH SSS) is made with Wikiwijs of Kennisnet. Wikiwijs is an educational platform where you can find, create and share learning materials.

- Author

- Last modified

- 04-09-2025 11:50:39

- License

-

This learning material is published under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license. This means that, as long as you give attribution, you are free to:

- Share - copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format

- Adapt - remix, transform, and build upon the material

- for any purpose, including commercial purposes.

More information about the CC Naamsvermelding 4.0 Internationale licentie.

Additional information about this learning material

The following additional information is available about this learning material:

- Description

- How to do literature research.

- Education level

- WO - Bachelor;

- Learning content and objectives

- Sociale wetenschappen;

- End user

- leerling/student

- Difficulty

- makkelijk

- Learning time

- 1 hour 0 minutes

Sources

| Source | Type |

|---|---|

|

Video UCLA Library: Mapping your research ideas https://youtu.be/jj-F6YVtsxI?si=sUAOpaJk91JrQNj8 |

Video |

|

Bron: York Library, Archives and Learning Services https://youtu.be/nYDAuT8sSco?si=JN7avqx4gRBR-UM7 |

Video |

Used Wikiwijs arrangements

E-learnings team informatiediensten. (2025).

Vinden van wetenschappelijke literatuur - stap voor stap (FSH SSW)

https://maken.wikiwijs.nl/213208/Vinden_van_wetenschappelijke_literatuur___stap_voor_stap__FSH_SSW_

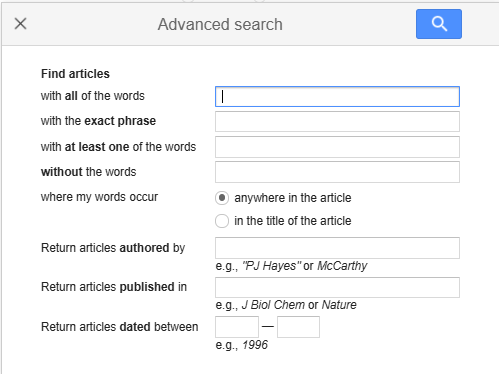

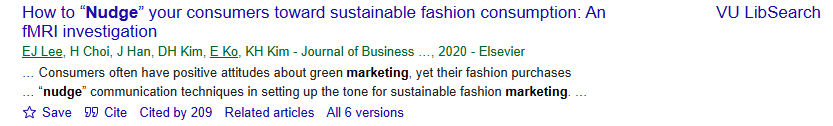

Article example in Google Scholar

Article example in Google Scholar Example of the same article in Scopus

Example of the same article in Scopus